South Beach Hoosier found these reviews while taking a break from digesting today's first round of the NFL Draft.

Naturally, this film is NOT likely to be playing in South Florida any time soon, despite the fact that the director sold her home in Miami in order to finance it.

I'll have to wait awhile to get my Hoosier fix. See also:

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0350142/ __________________________________________________________

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/04/26/AR2007042601570.html?nav=rss_print/style

Washington Post'Something to Cheer About': A Coach's Net Values

By Stephen Hunter, Washington Post Staff Writer

Friday, April 27, 2007

As nearly everyone who has ever dribbled a basketball knows, the most famous jump shot ever taken left the fingers of a young man on the night of March 20, 1954. The shooter was Bobby Plump, of tiny Milan, Ind. The ball went through the hoop, time ran out, and Milan became one of the smallest schools in Indiana history to win a state championship. Thus are legends born, then filmed, as "Hoosiers" was in 1986, with much fictionalization.

But . . . there's more. There's always more. The "more" kicked in the next year, when a school Milan beat on its way to the championship -- in the quarterfinals, 65-52 -- returned to the Indiana state tournament. That school was Crispus Attucks of Indianapolis. Attucks won the state championship in '55 and '56 (and again in '59), and sophomore guard Oscar Robertson went on to be an all-American at the University of Cincinnati and have a great NBA career. Attucks was the first all-black school -- it was a residue of the segregation then just beginning to loosen its grip on American society -- to win a state championship.

More to the point, as many would argue -- including the makers of the film "Something to Cheer About," an affectionate tribute to the Attucks program under the leadership of visionary coach Ray Crowe -- the success of Attucks changed basketball forever. The wide-open, driving, fast "black game" Crowe emphasized was just beginning to overcome and supplant the set-offense, slow-paced "white game." It signified what would be vouch-safed famously when the University of Texas-El Paso (then Texas Western), with five black starters, beat the University of Kentucky in 1966 for the NCAA championship.

One could even argue that the Milan victory was the high-water mark of white basketball, with its plodding offense, carefully regulated number of passes, and two-handed set shots. In fact, few remember that the game itself -- unless you had a rooting interest -- was rather boring. Milan played a slow-down offense to offset its opponents' power and speed (the opponent was a big-city school, Muncie Central) and Plump dribbled in place at the top of the key in the fourth quarter for four minutes with the score at 30-30, then took a shot -- and missed. Muncie rebounded, drove the court, but failed to score; the ball came back to Plump, who stalled, and then began the drive to the hoop for what would become his famous jumper. But the "Hoosiers" folks left out the 240 seconds of . . . nothingness . . . from the movie.

Whether or not there are such things as white basketball and black basketball, what is before us is a modest documentary, actually made in 2002 but only now gaining national release, which celebrates Attucks and that particular team, but most importantly coach Crowe, by all accounts a remarkable man.

It is said that in those days black teams, when they played white teams, were obligated to be gentlemen first and athletes second, to swallow the one-sided refereeing they were bound to receive, never to shower in the host school's facility and never to seem unsavorily preoccupied with winning.

Crowe changed that. A disciplinarian, he had one advantage in that he'd grown up around whites and didn't feel, as did many in segregated circumstances, uncomfortable in their presence. Liberated, therefore, from the pretense of "gentlemanly" behavior, he encouraged his players to run, shoot, jump and, most of all, win. But he was no run-and-gun guru: He counseled physical conditioning, disciplined offense, teamwork and obedience to his strict rules, which emphasized education as much as sports. And it must be said that he also was the beneficiary of extreme luck, with a roster including not only the one-in-a-million Big O, but also Hallie Bryant and Willie Merriweather, outstanding athletes who went on to college and then semipro and Harlem Globetrotter careers.

The filmmaker is Betsy Blankenbaker; she's not gifted and everything about the film is rudimentary, a mesh of old footage and stills (skillfully done) and talking heads (who do become tiresome). She evidently had access to Robertson for just one afternoon, and we never see him mingle with his former teammates (no reason is given). Instead, we see them, separately, at a celebration of their victory, old, dignified men, proud and strong but restrained. She got to Crowe in the last years of his life (he died in 2003), so that this remarkable man's wisdom, the force of his personality, his commitment to winning the right way or no way, are recorded.

Any hoop-dreamer of any color will enjoy the movie's brief 64 minutes.

Something to Cheer About (64 minutes, at Landmark's E Street Cinema) is not rated.

© 2007 The Washington Post Company

____________________________________________________________

Chicago Sun-TimesPlenty to 'Cheer' in hoops doc

April 27, 2007

BY

DAVE HOEKSTRA Staff Reporter

dhoekstra@suntimes.comThere has never been such a grandiose stage for the professional basketball player. During the NBA playoffs you will see a culture of players free-lancing, chest thumping and bringing bling to everything, including a seat at the end of the bench. I miss the congruent poetry of basketball, which is why I took to the loving documentary "Something to Cheer About."

The film's catalyst is Crispus Attucks High School in Indianapolis. In 1955 Attucks won the Indiana state championship, becoming the first all-black school in America to capture a state crown. The Tigers were led by future NBA Hall of Famer Oscar Robertson. A year later, Robertson took Attucks to another state title as it became the first Indiana prep team to complete an undefeated season.

Filmmaker Betsy Blankenbaker's father was a friend of Tigers head coach Ray Crowe (1950-57). She sold her Miami house to fund this 64-minute film, enlisted Robertson and former Tiger Willie Merriweather as co-producers, and embarked on gathering the important oral histories of the surviving players. Blankenbaker began her film in 2000. Four Tigers died during the project. Crowe died in 2003 at age 88, shortly after Blankenbaker finished "Something to Cheer About."

One of Blankenbaker's key acquisitions here is the grainy black and white footage of Crispus Attucks in action during the mid-1950s. It is stunning stuff. Check out the 1955 state championship between Crispus Attucks and Gary Roosevelt and dig the players' Chuck Taylor Hi Tops. Notice the way the team plays for a common goal.

Blankenbaker drives home the point that basketball was a community within a community at Crispus Attucks (the school was named after the African American who had been killed by British troops in the Boston Massacre that preceded the Revolutionary War). Nearly 14,000 fans attended Tigers games, although the team never had a home court. They played at Butler Fieldhouse, Arsenal Technical High School and along the countryside where some farmers had never seen African Americans. The team practiced in a 200-seat gym.

Crispus Attucks opened in 1927 and, according to Indianapolis legend, the Ku Klux Klan had a parade that celebrated the separation of black and white students. In the documentary, cheerleader Maxine Coleman recalled how students were taught to "represent ourselves and our parents wherever we went." Although Blankenbaker uses many present-day interviews, I wanted to learn more about what former players were doing today.

The Tigers had their own tune "The Crazy Song," which fans sang when victory was assured. Written by Attucks teacher Edwina Bell, "The Crazy Song" was not a pep rally song or spirit anthem, it was more of a doo-wop-meets-Cab Calloway number with swaying lyrics like "Hi-de-hi-de, hi-de-ho/That's the skip, bob beat-um/That's the crazy song." The song has a prominent place in "Something To Cheer About."

The dignified tone of the team was set by coach Crowe, a stern father figure. Crowe's players had to be in school in order to obtain playing time on the court. He benched players for what today would be termed as "trash talking." NBA great and Chicago native Isiah Thomas told Blankenbaker that black basketball coaches of this era were some of the "most inventive, free thinking" coaches in the game's history. Crowe deployed a liberating fast-break offense, and he was a pioneer in the democratic triangle offense that Tex Winter and Phil Jackson deployed during the Bulls' 1990s title runs.

Crowe emerges as the hero of "Something To Cheer About," while Robertson is the conscience. Thomas recalled Robertson's influence on his own career, citing Big O's line, "You play as you live."

How much can one coach influence a student?

Robertson earned a business degree at the University of Cincinnati. He was co-captain of the undefeated 1960 U.S. Olympic Team, when United States hoopsters excelled in the international arena. He was president of the NBA Players Association from 1965 until his retirement in 1974. And this season marks the 30th anniversary of the Oscar Robertson Rule, a 1976 class action settlement between the NBA and its players resulting from a lawsuit brought by Robertson six years earlier, which paved the way for free agency and changed the balance of power in pro sports. This legacy would have been unlikely without Crowe's imprint.

Robertson doesn't have as much face time in "Something to Cheer About" as Crowe, but Robertson's memories are stirring, notably when he admits he cannot get over the fact how the Tigers' 1955 and 1956 victory parades were diverted into the black community from the traditional downtown Indianapolis route.

"Something like this can bring a community together," Robertson said in a phone conversation earlier this week. "When we got into the state finals in 1955, cheerleaders from all the other schools came out to cheer for Crispus Attucks. We were known as Indianapolis Attucks and even headlines said the Indianapolis Attucks won the state title." In 2005 Robertson told the Indianapolis Star how the Tigers' success "sped up integration." Their triumphs were reported by the Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier.

The Golden State Warriors are in this year's NBA playoffs. When introduced, former Indiana Pacer Stephen Jackson conducts a fake police frisk with his hands behind his head. He's spoofing his charges of probation violation for discharging a firearm in an Indianapolis strip club parking lot. "Something To Cheer About" is for someone who wants to know about basketball in the compelling shadows before today's game.

These were cheers that changed America.

SOMETHING TO CHEER ABOUT (Not rated)

Critic's rating: Three Stars

Featuring: Oscar Robertson, Ray Crowe and others.

Truly Indie presents a documentary written and directed by Betsy Blankenbaker.

Running time: 64 minutes. No MPAA rating.

Opening today at Landmark Century.

© Copyright 2007 Sun-Times News Group

_____________________________________________________________

http://www.calendarlive.com/movies/reviews/cl-et-something27apr27,0,4281920.story

Los Angeles TimesMOVIE REVIEW 'Something to Cheer About'

A documentary revisits a mid-1950s basketball team.By Sam Adams

Special to The Times

April 27, 2007

In the documentary "Something to Cheer About," former players at Indianapolis' all-black Crispus Attucks high school recall having to step aside when white folks walked toward them on a busy sidewalk. But on the court, especially under the leadership of coach Ray Crowe, they made room for no one.

In 1955, Attucks became the first all-black team to win a state championship, a feat repeated for the next two years. Indiana Pacer Isaiah Thomas praises the "inventive and free-thinking" coaches of the era, while Sen. Richard Lugar calls Crowe's style, relying on frequent passing and fluid play, "a breakthrough in Indiana basketball."

The former Attucks players who line up for Betsy Blankenbaker's camera have a simpler explanation: Crowe taught them to win. Previous coaches were mainly concerned that the players comported themselves like gentlemen, no mean feat in a segregated era when the team had to travel long distances to find enough schools that would play them to make up a full season.

Crowe, who narrator Willie Merriweather says wanted the game to make the boys rather than the other way around, coached his players in life as well as basketball. Merriweather, later

All-American at Purdue, says he would have dropped out of high school if not for Crowe's paternal influence. But he also expected them to win games, which they did with astonishing and often unbroken regularity.

The most famous Attucks alumnus was Oscar Robertson, who went on to become a 12-time NBA All-Star during seasons with the Cincinnati Royals and Milwaukee Bucks. Thomas calls him "a great thinker of the game," but his fellow players recall him first as a scrawny kid who was allowed to join their pickup games only because he owned his own basketball. Robertson later grew to 6 feet 5, but the nickname "Big O" started out as a joke.

The players' memories amply document the inequities of segregation, recalling a time when they could sell 10,000 tickets to a game at Butler University's field house (having long since outgrown their own facilities) but were still not allowed to eat in the school's cafeteria. Attucks player Bill Hampton describes the prevalence of corrupt officiating, which effectively added the invariably white referees to the other team's roster. "You looked at it like you're playing [against] seven guys, and they're playing [against] five," he says.

But the movie could have had much greater resonance were it not focused so monolithically on basketball. One wonders what life was like at Attucks High, or how the players' success on the court affected their lives off it. Blankenbaker treats her subjects with respect, but always from a distance. The movie never gets under their skin or develops an emotional narrative to go with its historical recitation. It's full of abrupt leaps and blunt conclusions, redundancies and omissions (among them the fact that Attucks, after winning another title in 1959, never returned to the Final Four).

"Something to Cheer About" is the outline of a great story, but it never fills in the gaps.

"Something to Cheer About." MPAA rating: unrated.

Running time: 1 hour, 15 minutes.

Exclusively at Laemmle's Grande, 345 S. Figueroa St., downtown L.A , (213) 617-0268.

Copyright Los Angeles Times

______________________________________________

http://www.villagevoice.com/film/0717,wilonsky,76476,20.htmlThe Village Voice

Tracking Shots

'Something to Cheer About'

by Robert Wilonsky

April 24th, 2007

Something to Cheer About

Directed by Betsy Blankenbaker

Opens April 27, Quad Cinema

In 1927 Indianapolis, the Ku Klux Klan opened the all-black Crispus Attucks High School with the intention of keeping black children out of allegedly superior white schools. The plan backfired, and Attucks became one of the premier schools in the entire country. By the 1950s, it was also home to one of the greatest basketball teams in the country, led by future immortal Oscar Robertson. Several Attucks Tigers, all spry and thoughtful 50 years on, are on hand here to retrace old footsteps on the hardwood and claim their place in history, but Betsy Blankenbaker's doc doesn't possess the kinetic charge of the tale itself; it's too reliant on talking heads and faded photos. Cheer feels amateurish for a generation raised on sports films.

Shoulda been a slam-dunk too.

________________________________________________

http://movies2.nytimes.com/2007/04/27/movies/27chee.html

New York Times

April 27, 2007

MOVIE REVIEW

'SOMETHING TO CHEER ABOUT'

Victories Beyond the Basketball Court

By JEANNETTE CATSOULIS

Short, sweet and sentimental,

"Something to Cheer About" tells the story of Indiana's Crispus Attucks Tigers, who, in 1955, became the first all-black high school basketball team to win a state championship. Like last year's

"Glory Road,"Betsy Blankenbaker's documentary celebrates a victory over much more than just rival teams.Between grainy clips of game film, original team members like the legendary Oscar Robertson, a producer of the film, and the former Harlem Globetrotter Hallie Bryant recall a time when basketball was their release from poverty and segregation.

The team's unusually athletic playing style soon drew crowds of 10,000 and more while confounding its white opponents — who were eager to split the gate but not so eager to socialize afterward.

A trickier problem was the racism of many white officials. "We always believed we could beat any team that we played against," says the former player Stan Patton. "The only two people we had to beat were the referees."

Plodding but heartfelt, "Something to Cheer About" pays tribute to a time when basketball scholarships and professional opportunities were practically unknown.

Back then, a player's only opportunity was to make history.

SOMETHING TO CHEER ABOUT Opens today in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas, Detroit, Atlanta, Minneapolis, Indianapolis and Washington.

Written and directed by Betsy Blankenbaker; directors of photography, Robert Shepard and Dustin Teel; edited by Steve Marra; music by Steve Allee; produced by Ms. Blankenbaker, Willie Merriweather and Oscar Robertson; released by Truly Indie.

In Manhattan at the Quad Cinema, 34 West 13th Street, Greenwich Village.

Running time: 64 minutes.

This film is not rated.

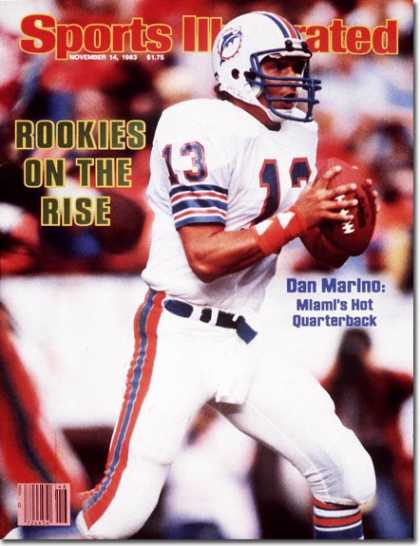

Fort Lauderdale International Film Festival promo card from 2004

Fort Lauderdale International Film Festival promo card from 2004

+Sep+10,+1984.jpg)